Product successfully added to your shopping cart

The Sticky Sweet Secret: How to Make Nian Gao Like a Local Grandmother

The air is thick with the scent of melted brown sugar and pandan leaves. In kitchens across Asia, as Lunar New Year approaches, a silent, sticky alchemy takes place. It’s the making of nian gao (年糕), the iconic steamed rice cake. More than just a treat, its name is a homophone for "higher year," symbolizing growth, promotion, and the sweet rising of fortunes. While store-bought versions abound, crafting your own is a ritual—a tangible hope for the new year passed from one generation to the next.

To make it like a local is to understand it’s not just cooking; it’s an act of faith and patience. Forget quick mixes. Here’s how to prepare the heart of CNY, one sticky, sweet slice at a time.

Phase 1: The Foundation – Choosing Your Spirit

There are two main paths: the classic brown sugar nian gao, deep, caramel-like, and robust, or the pandan coconut nian gao, vibrantly green and fragrant. The local secret? Your choice of sugar and rice defines everything.

-

The Rice: Locals don't use regular flour. They seek out glutinous rice flour (nuo mi fen). For the truest, chewiest texture, the old way involves soaking whole glutinous rice overnight and stone-grinding it into a wet, milky paste. For the home cook, a high-quality bag of finely milled glutinous rice flour is perfect. Pro-tip: Sift it. Always sift it. This ensures no lumps, leading to that impossibly smooth, jiggly finish.

-

The Sugar: For the classic version, slab dark brown sugar (pei tong) is non-negotiable. It’s sold in hard, rocky chunks and carries a complex molasses flavor. Melting it down with water is the first step, filling your kitchen with its rich perfume. For pandan cakes, white sugar and fresh pandan leaf juice provide the signature aroma.

-

The Water: The ratio is sacred. Too much, and the cake won’t set; too little, and it’s dense and hard. Locals judge by the consistency of the batter—it should be like heavy cream, coating the back of a spoon but still easily pourable.

Phase 2: The Alchemy – Mixing & Steaming with Intention

-

The Harmonious Batter: Dissolve your sugar completely in warm water or coconut milk. Let it cool to room temperature. Gradually whisk this liquid into your sifted flour. This is where mindfulness matters. Whisk until absolutely smooth, not just mostly smooth. Any tiny lumps will survive the steam and marr the perfect texture. Strain the batter through a fine sieve for guaranteed silkiness.

-

The Vessel: Traditionally, cakes are steamed in shallow, round metal tins or small porcelain bowls greased with a touch of oil. The round shape symbolizes reunion and completeness. Greasing is crucial—it’s the difference between a clean release and a frustrating stick-fest.

-

The Great Steam: This is a marathon, not a sprint. Place your filled tins in a steamer over vigorously boiling water. Cover the steamer lid with a cloth—this local hack prevents condensation from dripping onto the cake’s surface, creating craters. Steam on medium-high heat for a minimum of 4 to 6 hours, depending on size. Yes, hours. Top up the steamer with boiling water, never cold, to maintain constant temperature. The cake is done when a skewer inserted into the centre comes out clean.

Phase 3: The Test – Resting & The Knife Trick

The hardest part begins when the steaming ends. Do not touch it.

-

The Rest: Let the cake cool completely in its tin, then cover and let it rest at room temperature for at least 24-48 hours. This resting period is magical. The cake firms up, the sweetness mellows and distributes evenly, and the legendary sticky, chewy texture develops. Cutting into it too early is the most common beginner’s mistake—you’ll have a gooey, unset mess.

-

The Cut: To slice a rested nian gao, locals use the "Dip and Slice" method. Dip your knife or kitchen scissors in water (or oil) between every single cut. The sticky blade becomes a clean blade. For elegant pan-frying, slice it into even, 1cm-thick pieces.

Local’s Wisdom: Troubleshooting & Traditions

-

Too Soft/Not Setting: Likely under-steamed or batter was too wet. Next time, extend steaming time and slightly reduce liquid.

-

Too Hard/Dense: Batter was too thick or over-mixed after adding flour. Ensure correct liquid ratio and mix gently until just combined.

-

The Signature Eat: While delicious plain, locals love it pan-fried. Dip slices in lightly beaten egg and pan-fry until the exterior is crispy and the inside is soft and molten. It’s also steamed and served with sweet potato or tucked into a sandwich of sweet potato slices.

-

The Offering: A perfect, whole nian gao is placed on the family altar as an offering to the Kitchen God and ancestors, hoping for sweet words and blessings.

Making nian gao is an exercise in hope. The long steam is a meditation, the wait a lesson in anticipation. When you finally slice into your own creation—firm, glossy, and resilient—you’re tasting more than sugar and rice. You’re tasting a promise for the year ahead, made with your own hands. That’s the true local secret: the best ingredient is always intention.

Gong Xi Fa Cai. May your year rise sweet and high.

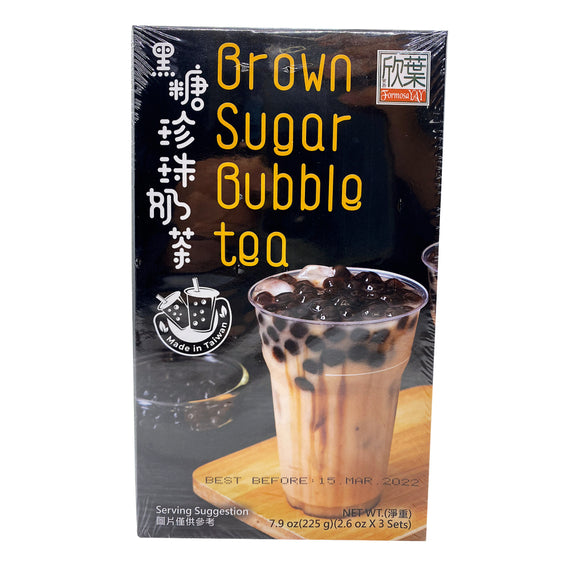

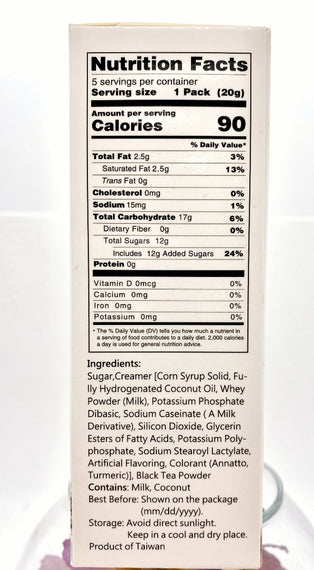

Net Weight: 520 g

Country of origin: Taiwan